Quiz-summary

0 of 30 questions completed

Questions:

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

Information

Premium Practice Questions

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading...

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You have to finish following quiz, to start this quiz:

Results

0 of 30 questions answered correctly

Your time:

Time has elapsed

Categories

- Not categorized 0%

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

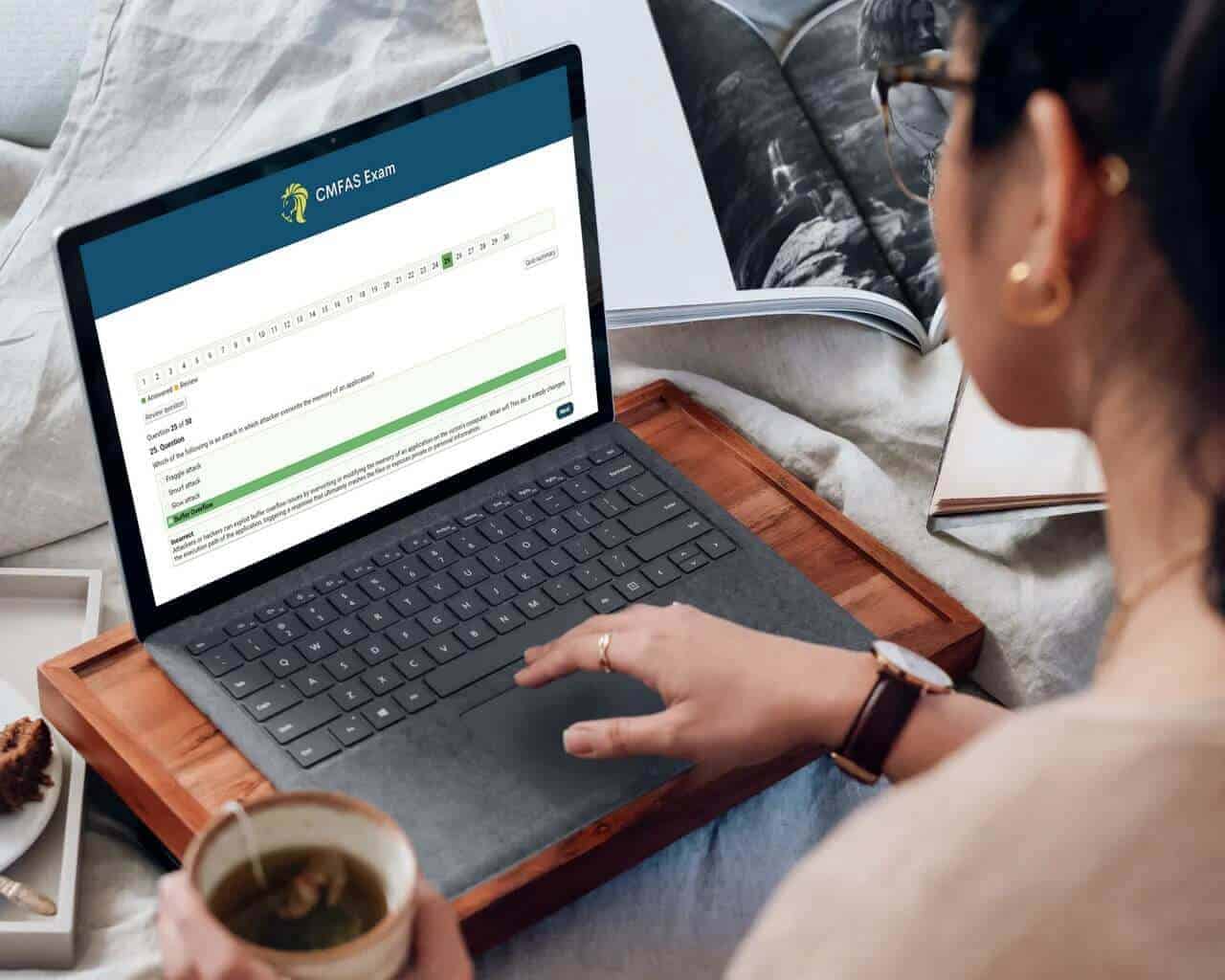

- Answered

- Review

-

Question 1 of 30

1. Question

A financial planner is reviewing a client’s comprehensive risk management plan to optimize strategies beyond traditional insurance products. The client seeks to understand how different techniques apply to their personal and professional exposures. Consider the following statements regarding personal risk management techniques:

I. Risk retention is generally the most cost-effective strategy for high-frequency, low-severity risks that can be funded through current cash flow.

II. Risk avoidance is characterized by the implementation of loss prevention measures, such as installing smoke detectors, to reduce the likelihood of a peril.

III. Non-insurance risk transfer involves shifting the financial consequences of a loss to another party through legal contracts other than insurance policies.

IV. Maintaining a dedicated emergency fund is a form of planned risk retention used to cover losses that fall below insurance deductible levels.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statements I, III, and IV are correct because they accurately define risk management pillars. Risk retention is the most efficient approach for high-frequency, low-severity losses that are predictable. Non-insurance transfers use legal contracts like hold-harmless agreements to shift liability to third parties. Emergency funds serve as a primary tool for active risk retention by covering small, manageable losses.

Incorrect: The strategy of labeling loss prevention as risk avoidance is technically incorrect. Risk avoidance requires the total elimination of an exposure by refusing to engage in the activity. Simply conducting safety measures like installing smoke detectors constitutes risk reduction or loss control. Focusing only on the reduction of probability ignores that avoidance leaves no residual risk at all. Pursuing a definition where all mitigation is avoidance fails to distinguish between stopping an action and making it safer.

Takeaway: Risk avoidance requires total elimination of an activity, whereas risk reduction focuses on decreasing the frequency or severity of potential losses.

Incorrect

Correct: Statements I, III, and IV are correct because they accurately define risk management pillars. Risk retention is the most efficient approach for high-frequency, low-severity losses that are predictable. Non-insurance transfers use legal contracts like hold-harmless agreements to shift liability to third parties. Emergency funds serve as a primary tool for active risk retention by covering small, manageable losses.

Incorrect: The strategy of labeling loss prevention as risk avoidance is technically incorrect. Risk avoidance requires the total elimination of an exposure by refusing to engage in the activity. Simply conducting safety measures like installing smoke detectors constitutes risk reduction or loss control. Focusing only on the reduction of probability ignores that avoidance leaves no residual risk at all. Pursuing a definition where all mitigation is avoidance fails to distinguish between stopping an action and making it safer.

Takeaway: Risk avoidance requires total elimination of an activity, whereas risk reduction focuses on decreasing the frequency or severity of potential losses.

-

Question 2 of 30

2. Question

A financial consultant is designing a non-qualified deferred compensation plan for a mid-sized U.S. corporation using Variable Universal Life (VUL) insurance as the primary funding vehicle. The corporate client is concerned about the overlapping regulatory requirements between state insurance departments and federal agencies. Specifically, the client’s legal team is debating whether the state’s insurance illustration model regulation takes precedence over SEC prospectus delivery requirements. Additionally, they are evaluating how the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) impacts the selection of the underlying investment subaccounts within the VUL policy. Which of the following best describes the regulatory framework governing this scenario?

Correct

Correct: Variable insurance products are hybrid instruments subject to dual regulation. The McCarran-Ferguson Act preserves state authority over the insurance aspects, such as solvency and policy terms. However, federal securities laws apply to the investment component because the policyholder assumes investment risk. When these products are used in employer-sponsored plans, ERISA Section 404(a) further mandates that fiduciaries act with care and loyalty in selecting subaccounts.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the McCarran-Ferguson Act to exclude federal oversight ignores the established legal precedent that variable contracts are securities. The strategy of assuming ERISA preemption eliminates all state insurance department authority fails to recognize the ERISA savings clause. This clause specifically preserves state power to regulate the business of insurance. Focusing only on the death benefit to claim exemption from federal investment laws overlooks the fact that separate accounts are regulated investment companies.

Takeaway: Variable life products require simultaneous compliance with state insurance laws, federal securities regulations, and ERISA fiduciary standards in corporate plan settings.

Incorrect

Correct: Variable insurance products are hybrid instruments subject to dual regulation. The McCarran-Ferguson Act preserves state authority over the insurance aspects, such as solvency and policy terms. However, federal securities laws apply to the investment component because the policyholder assumes investment risk. When these products are used in employer-sponsored plans, ERISA Section 404(a) further mandates that fiduciaries act with care and loyalty in selecting subaccounts.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the McCarran-Ferguson Act to exclude federal oversight ignores the established legal precedent that variable contracts are securities. The strategy of assuming ERISA preemption eliminates all state insurance department authority fails to recognize the ERISA savings clause. This clause specifically preserves state power to regulate the business of insurance. Focusing only on the death benefit to claim exemption from federal investment laws overlooks the fact that separate accounts are regulated investment companies.

Takeaway: Variable life products require simultaneous compliance with state insurance laws, federal securities regulations, and ERISA fiduciary standards in corporate plan settings.

-

Question 3 of 30

3. Question

An insurance producer in a state that has adopted the NAIC Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement Model Regulation is meeting with a 62-year-old client. The client wants to replace a 15-year-old whole life policy with a new indexed universal life policy to obtain more flexible premium payments. The producer observes that the existing policy has a substantial cash value and a guaranteed interest rate that is significantly higher than current market offerings. To maintain compliance with state regulations and the ethical standards of the CLU designation, the producer must navigate the disclosure process carefully. Which action is the most appropriate for the producer to take regarding the disclosure and processing of this replacement?

Correct

Correct: The NAIC Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement Model Regulation, adopted by most states, requires producers to provide a specific Notice Regarding Replacement to the applicant. This process ensures the client is fully informed about the loss of existing cash values, the reset of the two-year contestability period, and the start of a new suicide clause. Providing a detailed comparative information form is essential for the client to evaluate the trade-offs between the guaranteed features of the old policy and the flexibility of the new one.

Incorrect: Relying solely on verbal acknowledgments fails to meet the strict written disclosure requirements mandated by state insurance departments for replacement transactions. The strategy of waiting for a conservation proposal from the existing carrier is not a regulatory requirement for the producer and could cause unnecessary delays in the client’s financial planning. Focusing only on the increase in death benefit ignores the critical fiduciary duty to disclose the loss of favorable guaranteed interest rates and existing policy equity. Choosing to use a general liability waiver instead of state-mandated forms represents a significant compliance failure that leaves the producer and the insurer vulnerable to regulatory action.

Takeaway: Producers must provide specific written notices and comparative disclosures to ensure clients understand the risks and costs associated with replacing existing life insurance.

Incorrect

Correct: The NAIC Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement Model Regulation, adopted by most states, requires producers to provide a specific Notice Regarding Replacement to the applicant. This process ensures the client is fully informed about the loss of existing cash values, the reset of the two-year contestability period, and the start of a new suicide clause. Providing a detailed comparative information form is essential for the client to evaluate the trade-offs between the guaranteed features of the old policy and the flexibility of the new one.

Incorrect: Relying solely on verbal acknowledgments fails to meet the strict written disclosure requirements mandated by state insurance departments for replacement transactions. The strategy of waiting for a conservation proposal from the existing carrier is not a regulatory requirement for the producer and could cause unnecessary delays in the client’s financial planning. Focusing only on the increase in death benefit ignores the critical fiduciary duty to disclose the loss of favorable guaranteed interest rates and existing policy equity. Choosing to use a general liability waiver instead of state-mandated forms represents a significant compliance failure that leaves the producer and the insurer vulnerable to regulatory action.

Takeaway: Producers must provide specific written notices and comparative disclosures to ensure clients understand the risks and costs associated with replacing existing life insurance.

-

Question 4 of 30

4. Question

A policyholder, Sarah, purchased a $500,000 whole life insurance policy in the United States 14 months ago. She recently died in a car accident. During the routine claims investigation, the insurance company discovered that Sarah listed her age as 34 on the application, but her birth certificate confirms she was actually 37 at the time of issuance. The insurer determines that the premium she paid would have only purchased $440,000 of coverage had her true age been known. How must the insurer handle the claim settlement under standard U.S. life insurance policy provisions and state insurance laws?

Correct

Correct: The Misstatement of Age provision is a mandatory clause in most states that operates independently of the incontestability clause. It requires the insurer to adjust the death benefit to the amount the premiums paid would have purchased at the insured’s correct age. This provision protects the insurer’s actuarial integrity while ensuring the beneficiary still receives a proportional benefit despite the application error.

Incorrect: Relying on the incontestability period to mandate full payment is incorrect because age and sex misstatements are specifically excluded from incontestability protections in standard U.S. policy language. The strategy of rescinding the policy for material misrepresentation is legally impermissible for age errors under standard state insurance regulations. Choosing to deduct back-premiums from the face amount is an incorrect application of the law, as the standard requires adjusting the total coverage amount instead.

Takeaway: Age misstatements lead to a proportional adjustment of the death benefit rather than policy cancellation or full face value payment.

Incorrect

Correct: The Misstatement of Age provision is a mandatory clause in most states that operates independently of the incontestability clause. It requires the insurer to adjust the death benefit to the amount the premiums paid would have purchased at the insured’s correct age. This provision protects the insurer’s actuarial integrity while ensuring the beneficiary still receives a proportional benefit despite the application error.

Incorrect: Relying on the incontestability period to mandate full payment is incorrect because age and sex misstatements are specifically excluded from incontestability protections in standard U.S. policy language. The strategy of rescinding the policy for material misrepresentation is legally impermissible for age errors under standard state insurance regulations. Choosing to deduct back-premiums from the face amount is an incorrect application of the law, as the standard requires adjusting the total coverage amount instead.

Takeaway: Age misstatements lead to a proportional adjustment of the death benefit rather than policy cancellation or full face value payment.

-

Question 5 of 30

5. Question

A senior underwriter at a United States insurance carrier is reviewing an application for a high-limit individual disability income policy. The applicant is a corporate executive who earns a substantial salary but also receives significant annual dividends from a private family trust. The executive’s role involves frequent travel and occasional site visits to manufacturing facilities. Consider the following statements regarding the underwriting principles for this disability income insurance case:

I. Financial underwriting aims to replace a portion of earned income while preventing over-insurance that might discourage the insured from returning to work.

II. The occupational classification is determined primarily by the specific daily duties the applicant performs rather than the formal job title provided.

III. Passive unearned income, such as interest and dividends, is generally added to earned income to increase the maximum monthly benefit the underwriter will approve.

IV. Underwriters utilize morbidity tables to assess the probability and potential length of a disability claim rather than mortality tables.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statement I is correct because disability income underwriting must prevent over-insurance to ensure the insured has a financial incentive to return to work. Statement II is accurate as underwriters prioritize actual job duties over titles to determine the true risk of injury or illness. Statement IV is correct because morbidity tables specifically measure the frequency and duration of disability, which is the primary risk being insured.

Incorrect: The strategy of including passive unearned income in the earned income calculation is incorrect because such income continues regardless of the insured’s ability to work. Relying on combinations that omit the importance of specific job duties fails to recognize that physical and environmental exposures dictate risk classes. Focusing on combinations that exclude morbidity data ignores the fundamental actuarial basis for pricing disability risks compared to life insurance. Choosing to ignore the principle of over-insurance overlooks the moral hazard created when disability benefits approach or exceed net take-home pay.

Takeaway: DI underwriting focuses on earned income replacement, specific occupational duties, and morbidity data to manage risk and maintain work incentives.

Incorrect

Correct: Statement I is correct because disability income underwriting must prevent over-insurance to ensure the insured has a financial incentive to return to work. Statement II is accurate as underwriters prioritize actual job duties over titles to determine the true risk of injury or illness. Statement IV is correct because morbidity tables specifically measure the frequency and duration of disability, which is the primary risk being insured.

Incorrect: The strategy of including passive unearned income in the earned income calculation is incorrect because such income continues regardless of the insured’s ability to work. Relying on combinations that omit the importance of specific job duties fails to recognize that physical and environmental exposures dictate risk classes. Focusing on combinations that exclude morbidity data ignores the fundamental actuarial basis for pricing disability risks compared to life insurance. Choosing to ignore the principle of over-insurance overlooks the moral hazard created when disability benefits approach or exceed net take-home pay.

Takeaway: DI underwriting focuses on earned income replacement, specific occupational duties, and morbidity data to manage risk and maintain work incentives.

-

Question 6 of 30

6. Question

A financial consultant is evaluating a retirement income strategy for a 62-year-old client who is concerned about sequence-of-returns risk but remains interested in equity market participation. The consultant is reviewing several innovative annuity structures and the current regulatory environment in the United States to ensure the recommendation aligns with modern product trends and compliance standards. Consider the following statements regarding current annuity innovations and regulations:

I. Registered Index-Linked Annuities (RILAs) have grown in popularity by offering a ‘buffer’ or ‘floor’ against market losses while providing higher growth potential than traditional fixed indexed annuities.

II. The SEC’s Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) requires broker-dealers to act in the best interest of retail customers when recommending annuity products that are classified as securities.

III. Multi-Year Guaranteed Annuities (MYGAs) are classified as variable products by the SEC because their interest rates are tied to the daily performance of the S&P 500 index.

IV. Recent innovations include the integration of Long-Term Care (LTC) riders that allow for tax-free distributions for qualified care expenses under Internal Revenue Code Section 7702B.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statement I is correct because Registered Index-Linked Annuities (RILAs) utilize buffers or floors to mitigate downside risk while allowing for higher participation in market gains. Statement II is correct as the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) mandates that broker-dealers prioritize the client’s interest over their own when recommending annuities. Statement IV is correct because Internal Revenue Code Section 7702B provides the legal framework for tax-free distributions from annuity-based long-term care riders.

Incorrect: The assertion that Multi-Year Guaranteed Annuities (MYGAs) are variable products is incorrect because they are fixed annuities offering a set interest rate for a specific duration. Focusing only on the first two statements is insufficient as it ignores the critical tax-advantaged innovations in long-term care hybrid products. The strategy of including all four statements fails because it incorrectly attributes equity index performance to MYGAs, which are actually fixed-rate instruments.

Takeaway: Annuity professionals must differentiate between RILAs, MYGAs, and hybrid LTC riders while complying with SEC Regulation Best Interest standards.

Incorrect

Correct: Statement I is correct because Registered Index-Linked Annuities (RILAs) utilize buffers or floors to mitigate downside risk while allowing for higher participation in market gains. Statement II is correct as the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) mandates that broker-dealers prioritize the client’s interest over their own when recommending annuities. Statement IV is correct because Internal Revenue Code Section 7702B provides the legal framework for tax-free distributions from annuity-based long-term care riders.

Incorrect: The assertion that Multi-Year Guaranteed Annuities (MYGAs) are variable products is incorrect because they are fixed annuities offering a set interest rate for a specific duration. Focusing only on the first two statements is insufficient as it ignores the critical tax-advantaged innovations in long-term care hybrid products. The strategy of including all four statements fails because it incorrectly attributes equity index performance to MYGAs, which are actually fixed-rate instruments.

Takeaway: Annuity professionals must differentiate between RILAs, MYGAs, and hybrid LTC riders while complying with SEC Regulation Best Interest standards.

-

Question 7 of 30

7. Question

A client, Sarah, owns a whole life insurance policy issued in the United States that lapsed 18 months ago due to non-payment of premiums. She now wishes to reinstate the policy to maintain the original premium rate and cash value accumulation schedule. Since the lapse, Sarah has been diagnosed with mild hypertension, which is currently well-controlled with medication. The original policy contained a standard two-year incontestability clause, and the initial two-year period had already expired before the lapse occurred. Sarah submits the required back premiums plus interest and an application for reinstatement. How must the insurer treat the incontestability provision upon successful reinstatement of this policy under standard industry practices?

Correct

Correct: Under standard United States life insurance provisions and state insurance laws, reinstatement typically initiates a new contestability period. This new period applies specifically to the representations made in the reinstatement application. The insurer retains the right to contest the policy for a new two-year period if material misrepresentations were made during the reinstatement process. However, the insurer cannot re-open the contestability of the original application if the initial two-year period had already expired before the lapse occurred.

Incorrect: The strategy of assuming the incontestability period remains permanently expired fails to account for the legal distinction between the original contract and the reinstatement application. Focusing only on the original expiration date ignores the insurer’s right to rely on truthful health disclosures during the policy’s revival. Pursuing a full reset of the original contestability period for the entire policy is generally prohibited by state regulations once the initial timeframe has passed. Choosing to waive the contestability period based on meeting current underwriting standards incorrectly implies that the legal right to contest is tied to the risk level rather than the application’s integrity.

Takeaway: Reinstatement creates a new contestability period limited to the information provided in the reinstatement application, while the original period remains expired.

Incorrect

Correct: Under standard United States life insurance provisions and state insurance laws, reinstatement typically initiates a new contestability period. This new period applies specifically to the representations made in the reinstatement application. The insurer retains the right to contest the policy for a new two-year period if material misrepresentations were made during the reinstatement process. However, the insurer cannot re-open the contestability of the original application if the initial two-year period had already expired before the lapse occurred.

Incorrect: The strategy of assuming the incontestability period remains permanently expired fails to account for the legal distinction between the original contract and the reinstatement application. Focusing only on the original expiration date ignores the insurer’s right to rely on truthful health disclosures during the policy’s revival. Pursuing a full reset of the original contestability period for the entire policy is generally prohibited by state regulations once the initial timeframe has passed. Choosing to waive the contestability period based on meeting current underwriting standards incorrectly implies that the legal right to contest is tied to the risk level rather than the application’s integrity.

Takeaway: Reinstatement creates a new contestability period limited to the information provided in the reinstatement application, while the original period remains expired.

-

Question 8 of 30

8. Question

James, a 62-year-old executive, holds a $500,000 whole life insurance policy with significant cash value and a 4% guaranteed internal rate of return. He expresses interest in replacing this policy with a Variable Universal Life (VUL) policy to pursue higher equity-linked growth as he approaches retirement. James is concerned about the current dividend scale of his whole life policy but values the death benefit for estate liquidity. His risk profile is moderate, and he has no other significant equity exposure. You must evaluate the replacement under the NAIC Life Insurance Replacements Model Regulation and applicable best interest standards. Which course of action best demonstrates professional advocacy and adherence to regulatory standards?

Correct

Correct: The correct approach adheres to the NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation and the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest by requiring a side-by-side comparison of policy guarantees and costs. It ensures the client understands the loss of existing guarantees and the implications of a new contestability period. This method prioritizes the client’s long-term financial security over short-term market potential. It also fulfills the fiduciary-like duty of care by documenting how the increased risk of a variable product specifically fits the client’s profile.

Incorrect: Relying solely on historical performance data fails to account for the volatility and potential for loss inherent in variable universal life products. Simply conducting a replacement based on verbal dissatisfaction ignores the professional obligation to perform a rigorous quantitative analysis of the existing policy’s intrinsic value. The strategy of focusing primarily on the tax-free nature of a Section 1035 exchange neglects the significant impact of new surrender charges and acquisition costs. Focusing only on premium flexibility overlooks the critical importance of maintaining death benefit guarantees for a client nearing retirement.

Takeaway: A best-interest replacement requires a comprehensive comparison of guarantees, costs, and risk alignment beyond simple tax advantages or historical performance.

Incorrect

Correct: The correct approach adheres to the NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation and the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest by requiring a side-by-side comparison of policy guarantees and costs. It ensures the client understands the loss of existing guarantees and the implications of a new contestability period. This method prioritizes the client’s long-term financial security over short-term market potential. It also fulfills the fiduciary-like duty of care by documenting how the increased risk of a variable product specifically fits the client’s profile.

Incorrect: Relying solely on historical performance data fails to account for the volatility and potential for loss inherent in variable universal life products. Simply conducting a replacement based on verbal dissatisfaction ignores the professional obligation to perform a rigorous quantitative analysis of the existing policy’s intrinsic value. The strategy of focusing primarily on the tax-free nature of a Section 1035 exchange neglects the significant impact of new surrender charges and acquisition costs. Focusing only on premium flexibility overlooks the critical importance of maintaining death benefit guarantees for a client nearing retirement.

Takeaway: A best-interest replacement requires a comprehensive comparison of guarantees, costs, and risk alignment beyond simple tax advantages or historical performance.

-

Question 9 of 30

9. Question

TechFab Inc., a mid-sized manufacturing firm in the United States, maintains a $5 million key person life insurance policy on its founder, who plans to retire in three years. To ensure long-term sustainability and manage corporate risk, the board is evaluating how to transition this asset to support a supplemental executive retirement plan (SERP). The board must remain compliant with Internal Revenue Code Section 101(j) notice and consent requirements to preserve the tax-free nature of the death benefit. Which strategy best balances the corporation’s need for risk management, tax efficiency, and long-term financial sustainability?

Correct

Correct: Transitioning the policy to fund a deferred compensation liability preserves the tax-advantaged status of the cash value under Internal Revenue Code guidelines. Maintaining compliance with Section 101(j) and Form 8925 reporting ensures the death benefit remains tax-free to the corporation. This approach provides a sustainable funding mechanism for future executive obligations without triggering immediate tax liabilities. It effectively balances corporate risk mitigation with long-term financial planning objectives.

Incorrect: Choosing to surrender the policy for immediate reinvestment triggers potential income tax on gains and forfeits the tax-free death benefit. The strategy of transferring ownership directly to the founder creates a substantial immediate taxable event for the executive. Opting for a split-dollar arrangement without addressing the SERP liability fails to align the asset with the corporation’s long-term financial sustainability goals. Focusing only on immediate liquidity ignores the long-term tax-efficiency of permanent life insurance.

Takeaway: Aligning life insurance assets with long-term liabilities requires strict adherence to IRC Section 101(j) and proactive tax-deferred growth management.

Incorrect

Correct: Transitioning the policy to fund a deferred compensation liability preserves the tax-advantaged status of the cash value under Internal Revenue Code guidelines. Maintaining compliance with Section 101(j) and Form 8925 reporting ensures the death benefit remains tax-free to the corporation. This approach provides a sustainable funding mechanism for future executive obligations without triggering immediate tax liabilities. It effectively balances corporate risk mitigation with long-term financial planning objectives.

Incorrect: Choosing to surrender the policy for immediate reinvestment triggers potential income tax on gains and forfeits the tax-free death benefit. The strategy of transferring ownership directly to the founder creates a substantial immediate taxable event for the executive. Opting for a split-dollar arrangement without addressing the SERP liability fails to align the asset with the corporation’s long-term financial sustainability goals. Focusing only on immediate liquidity ignores the long-term tax-efficiency of permanent life insurance.

Takeaway: Aligning life insurance assets with long-term liabilities requires strict adherence to IRC Section 101(j) and proactive tax-deferred growth management.

-

Question 10 of 30

10. Question

A mid-sized manufacturing firm in Ohio is restructuring its employee benefits package to better manage cash flow volatility. The CFO is comparing the regulatory requirements and operational constraints of a traditional profit-sharing plan versus a money purchase pension plan. The firm currently employs 150 people and wants to maximize tax-deductible contributions while maintaining some level of annual funding discretion. Consider the following statements regarding these defined contribution plans:

I. Profit-sharing plans allow for discretionary employer contributions, providing financial flexibility during periods of fluctuating corporate earnings.

II. Money purchase pension plans mandate a specific contribution formula, and failure to meet this funding requirement can result in IRS excise taxes.

III. Both plans are subject to the 25% of total participant compensation limit for employer tax deductions under Section 404 of the Internal Revenue Code.

IV. Money purchase pension plans permit participants to withdraw employer contributions for any reason after two years of plan participation, similar to profit-sharing plans.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statements I, II, and III correctly identify the core characteristics of these plans. Profit-sharing plans provide flexibility for employers to adjust contributions based on business performance. Money purchase plans are pension plans subject to IRC Section 412 minimum funding standards. Both plans share the same 25% of aggregate compensation deduction limit for the employer under the Internal Revenue Code.

Incorrect: The assertion that money purchase plans allow easy two-year withdrawals is incorrect because pension plans generally restrict distributions until retirement or termination. Relying on the idea that money purchase plans have higher deduction limits than profit-sharing plans is outdated since tax law changes equalized them. Focusing only on discretionary funding ignores the mandatory nature of money purchase pension plans. The strategy of treating both plans as having identical withdrawal flexibility fails to recognize the stricter pension designation of money purchase plans.

Takeaway: Profit-sharing plans offer funding flexibility, while money purchase plans require mandatory contributions, though both share the same 25% employer deduction limit.

Incorrect

Correct: Statements I, II, and III correctly identify the core characteristics of these plans. Profit-sharing plans provide flexibility for employers to adjust contributions based on business performance. Money purchase plans are pension plans subject to IRC Section 412 minimum funding standards. Both plans share the same 25% of aggregate compensation deduction limit for the employer under the Internal Revenue Code.

Incorrect: The assertion that money purchase plans allow easy two-year withdrawals is incorrect because pension plans generally restrict distributions until retirement or termination. Relying on the idea that money purchase plans have higher deduction limits than profit-sharing plans is outdated since tax law changes equalized them. Focusing only on discretionary funding ignores the mandatory nature of money purchase pension plans. The strategy of treating both plans as having identical withdrawal flexibility fails to recognize the stricter pension designation of money purchase plans.

Takeaway: Profit-sharing plans offer funding flexibility, while money purchase plans require mandatory contributions, though both share the same 25% employer deduction limit.

-

Question 11 of 30

11. Question

A senior partner at a prominent life insurance agency discovers that a top producer has been using non-compliant sales illustrations for high-net-worth whole life cases. These illustrations significantly overstated non-guaranteed dividend projections by using historical data from an era of much higher interest rates. Several policies have already been issued, and the firm’s internal compliance review confirms the error was intentional. The agency must now decide how to manage the resulting reputational and regulatory risks. Which course of action best reflects the ethical standards of a Chartered Life Underwriter while protecting the firm’s long-term standing?

Correct

Correct: Proactively notifying clients and self-reporting to regulators demonstrates a commitment to the CLU Code of Ethics. This strategy prioritizes transparency and client welfare over short-term financial stability. It aligns with FINRA Rule 2010 regarding standards of commercial honor. Such actions help mitigate long-term reputational damage by showing accountability. Regulatory bodies often view self-reporting as a mitigating factor during enforcement actions.

Incorrect: The strategy of terminating the agent and updating software fails to remediate the existing harm to current policyholders. Simply conducting case-by-case reviews as clients reach out ignores the proactive duty to disclose material errors. Pursuing a strategy focused on legal liability and general public statements prioritizes risk avoidance over ethical transparency. Focusing only on internal audits without client outreach does not satisfy the professional standards of a fiduciary.

Takeaway: Manage reputational risk by prioritizing proactive transparency and ethical accountability over reactive legal defense or internal-only corrections.

Incorrect

Correct: Proactively notifying clients and self-reporting to regulators demonstrates a commitment to the CLU Code of Ethics. This strategy prioritizes transparency and client welfare over short-term financial stability. It aligns with FINRA Rule 2010 regarding standards of commercial honor. Such actions help mitigate long-term reputational damage by showing accountability. Regulatory bodies often view self-reporting as a mitigating factor during enforcement actions.

Incorrect: The strategy of terminating the agent and updating software fails to remediate the existing harm to current policyholders. Simply conducting case-by-case reviews as clients reach out ignores the proactive duty to disclose material errors. Pursuing a strategy focused on legal liability and general public statements prioritizes risk avoidance over ethical transparency. Focusing only on internal audits without client outreach does not satisfy the professional standards of a fiduciary.

Takeaway: Manage reputational risk by prioritizing proactive transparency and ethical accountability over reactive legal defense or internal-only corrections.

-

Question 12 of 30

12. Question

Sarah is a 42-year-old specialized vascular surgeon with a high debt-to-income ratio due to recent practice expansion. While she maintains significant life insurance and a robust medical expense policy, her advisor identifies a gap in her protection against long-term morbidity. Sarah argues that her liquid savings could cover six months of expenses and that her life insurance includes a waiver of premium rider. What is the primary purpose of disability income insurance in this comprehensive financial plan, and how does it function relative to other risk management tools?

Correct

Correct: Disability income insurance is designed to protect the insured’s most valuable asset, their ability to earn an income, by providing periodic payments during periods of incapacity. This coverage ensures that the insured can meet ongoing financial obligations and avoid depleting retirement savings when they are unable to perform their professional duties. It functions as a replacement for the human life value that is lost when morbidity prevents active employment.

Incorrect: Focusing on lump-sum payments for medical expenses describes critical illness insurance, which does not provide the ongoing income replacement needed for daily living. The method of reimbursing specific out-of-pocket costs is the function of medical expense insurance, not the replacement of the insured’s human life value. Relying solely on life insurance riders like waiver of premium only maintains the policy’s force without addressing the household’s broader cash flow requirements.

Takeaway: Disability income insurance protects the insured’s earning capacity to ensure financial stability during periods of morbidity.

Incorrect

Correct: Disability income insurance is designed to protect the insured’s most valuable asset, their ability to earn an income, by providing periodic payments during periods of incapacity. This coverage ensures that the insured can meet ongoing financial obligations and avoid depleting retirement savings when they are unable to perform their professional duties. It functions as a replacement for the human life value that is lost when morbidity prevents active employment.

Incorrect: Focusing on lump-sum payments for medical expenses describes critical illness insurance, which does not provide the ongoing income replacement needed for daily living. The method of reimbursing specific out-of-pocket costs is the function of medical expense insurance, not the replacement of the insured’s human life value. Relying solely on life insurance riders like waiver of premium only maintains the policy’s force without addressing the household’s broader cash flow requirements.

Takeaway: Disability income insurance protects the insured’s earning capacity to ensure financial stability during periods of morbidity.

-

Question 13 of 30

13. Question

A financial professional is reviewing a non-qualified immediate annuity for a 72-year-old client, Mr. Henderson, who recently retired. Mr. Henderson invested $200,000 of after-tax savings into the contract and is scheduled to receive $1,500 monthly for life. He is concerned about the long-term tax implications if he lives well into his 90s, exceeding the life expectancy tables used to calculate his initial exclusion ratio. According to United States federal tax law and IRS Section 72, how should the tax treatment of his annuity payments be managed over the life of the contract?

Correct

Correct: Under Internal Revenue Code Section 72, non-qualified annuity payments are taxed using an exclusion ratio to separate the return of principal from taxable earnings. This ratio is calculated by dividing the investment in the contract by the expected return. Once the annuitant outlives their life expectancy and fully recovers their cost basis, all subsequent payments are treated as ordinary income. This ensures that the tax-free portion is limited to the actual after-tax dollars originally invested.

Incorrect: The strategy of treating earnings as long-term capital gains is incorrect because the IRS mandates that all annuity growth be taxed at ordinary income rates. Maintaining the exclusion ratio for the entire duration of the contract fails to account for the 1986 Tax Reform Act. This act requires full taxation of payments once the principal is exhausted. Relying on a first-in, first-out (FIFO) approach is inappropriate for annuitized periodic payments. Such payments must follow pro-rata exclusion rules rather than recovering the entire cost basis before any tax is owed.

Takeaway: Non-qualified annuity payments use an exclusion ratio until the cost basis is recovered, after which all payments become fully taxable.

Incorrect

Correct: Under Internal Revenue Code Section 72, non-qualified annuity payments are taxed using an exclusion ratio to separate the return of principal from taxable earnings. This ratio is calculated by dividing the investment in the contract by the expected return. Once the annuitant outlives their life expectancy and fully recovers their cost basis, all subsequent payments are treated as ordinary income. This ensures that the tax-free portion is limited to the actual after-tax dollars originally invested.

Incorrect: The strategy of treating earnings as long-term capital gains is incorrect because the IRS mandates that all annuity growth be taxed at ordinary income rates. Maintaining the exclusion ratio for the entire duration of the contract fails to account for the 1986 Tax Reform Act. This act requires full taxation of payments once the principal is exhausted. Relying on a first-in, first-out (FIFO) approach is inappropriate for annuitized periodic payments. Such payments must follow pro-rata exclusion rules rather than recovering the entire cost basis before any tax is owed.

Takeaway: Non-qualified annuity payments use an exclusion ratio until the cost basis is recovered, after which all payments become fully taxable.

-

Question 14 of 30

14. Question

A large multi-line insurance conglomerate based in New York is finalizing the acquisition of a mid-sized life insurance carrier domiciled in Ohio. The acquisition involves a 100% stock purchase, effectively transferring control of the Ohio carrier’s entire book of whole life and universal life business. While the federal antitrust review under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act has been completed, the legal teams must now address the specific insurance regulatory requirements to finalize the change of control. The acquiring firm must demonstrate that the merger will not result in a hazardous financial condition for the existing policyholders. Which action represents the mandatory regulatory procedure required to obtain approval for this change of control at the state level?

Correct

Correct: Under the Model Insurance Holding Company System Regulatory Act, any entity seeking to acquire control of a domestic insurer must file a Form A statement. The state insurance commissioner reviews this to ensure the acquirer’s financial condition does not jeopardize policyholder interests. This process specifically evaluates if the acquisition would substantially lessen competition or be hazardous to the public. It is the primary regulatory hurdle for insurance-specific change of control in the United States.

Incorrect: Relying solely on federal SEC Schedule 13D filings is insufficient because these disclosures focus on investor transparency rather than the specific solvency requirements of state insurance departments. The strategy of using Hart-Scott-Rodino Act clearance fails to address the unique policyholder protection standards required by state regulators. Choosing to prioritize a policyholder vote as a means to bypass regulatory hearings is incorrect because the insurance commissioner retains statutory authority to approve or deny the transaction. Focusing only on the target company’s board approval ignores the mandatory regulatory oversight required for the transfer of insurance licenses.

Takeaway: Insurance mergers require state-level Form A approval to ensure the acquirer is financially fit to protect existing policyholders.

Incorrect

Correct: Under the Model Insurance Holding Company System Regulatory Act, any entity seeking to acquire control of a domestic insurer must file a Form A statement. The state insurance commissioner reviews this to ensure the acquirer’s financial condition does not jeopardize policyholder interests. This process specifically evaluates if the acquisition would substantially lessen competition or be hazardous to the public. It is the primary regulatory hurdle for insurance-specific change of control in the United States.

Incorrect: Relying solely on federal SEC Schedule 13D filings is insufficient because these disclosures focus on investor transparency rather than the specific solvency requirements of state insurance departments. The strategy of using Hart-Scott-Rodino Act clearance fails to address the unique policyholder protection standards required by state regulators. Choosing to prioritize a policyholder vote as a means to bypass regulatory hearings is incorrect because the insurance commissioner retains statutory authority to approve or deny the transaction. Focusing only on the target company’s board approval ignores the mandatory regulatory oversight required for the transfer of insurance licenses.

Takeaway: Insurance mergers require state-level Form A approval to ensure the acquirer is financially fit to protect existing policyholders.

-

Question 15 of 30

15. Question

Robert, a resident of a state that follows the majority rule regarding life insurance exemptions, owns a $1,000,000 whole life policy with a $200,000 cash value. His wife is the named beneficiary. Robert is currently facing a significant civil judgment following a failed business venture. He is concerned about whether the judgment creditor can attach the cash value of the policy or if the death benefit will be protected for his wife. Which combination of factors most accurately determines the level of protection Robert’s life insurance policy receives from his creditors under typical U.S. state law?

Correct

Correct: State statutes are the primary source of protection, often requiring the beneficiary to be a spouse or child to trigger the exemption. Courts also examine the timing of payments to ensure the policyowner did not engage in fraudulent transfers to hide assets from known creditors.

Incorrect: Relying solely on federal bankruptcy exemptions is insufficient because many states require the use of state-specific exemptions that may have different limits. The strategy of invoking spendthrift clauses fails in this context because those provisions protect the beneficiary’s interest from their own creditors. Focusing only on ERISA protections is a fundamental error as individual life insurance policies not part of an employer-sponsored plan do not fall under ERISA’s jurisdiction.

Takeaway: Life insurance creditor protection is primarily a matter of state law and depends heavily on the beneficiary relationship and the absence of fraud.

Incorrect

Correct: State statutes are the primary source of protection, often requiring the beneficiary to be a spouse or child to trigger the exemption. Courts also examine the timing of payments to ensure the policyowner did not engage in fraudulent transfers to hide assets from known creditors.

Incorrect: Relying solely on federal bankruptcy exemptions is insufficient because many states require the use of state-specific exemptions that may have different limits. The strategy of invoking spendthrift clauses fails in this context because those provisions protect the beneficiary’s interest from their own creditors. Focusing only on ERISA protections is a fundamental error as individual life insurance policies not part of an employer-sponsored plan do not fall under ERISA’s jurisdiction.

Takeaway: Life insurance creditor protection is primarily a matter of state law and depends heavily on the beneficiary relationship and the absence of fraud.

-

Question 16 of 30

16. Question

Sarah, a CLU professional, manages a $5 million whole life policy for Mr. Thompson. His business partner, who is also Sarah’s client, requests the policy’s current cash value to update their buy-sell agreement valuation for an urgent board meeting. The partner claims Mr. Thompson gave verbal permission during a recent meeting and notes that the business entity pays the policy premiums. Sarah must balance the urgency of the business request with federal privacy standards. What is the most appropriate action for Sarah to take to ensure compliance with federal privacy regulations and professional ethical standards?

Correct

Correct: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act and Regulation S-P mandate that financial professionals protect nonpublic personal information from unauthorized disclosure. Obtaining formal written authorization ensures a verifiable legal record that the client consented to the specific release of sensitive contract data. This approach prioritizes the client’s privacy rights over the convenience of third parties or business partners.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the business relationship or the source of premium payments fails to respect the individual’s legal right to privacy regarding their specific insurance contract. The strategy of disclosing information while simultaneously notifying the client via email does not satisfy the regulatory requirement for prior consent. Opting for verbal confirmation on a recorded line lacks the formal documentation necessary to protect against future disputes or regulatory audits during compliance reviews.

Takeaway: Secure written authorization before disclosing nonpublic personal information to any third party to ensure compliance with federal privacy laws.

Incorrect

Correct: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act and Regulation S-P mandate that financial professionals protect nonpublic personal information from unauthorized disclosure. Obtaining formal written authorization ensures a verifiable legal record that the client consented to the specific release of sensitive contract data. This approach prioritizes the client’s privacy rights over the convenience of third parties or business partners.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the business relationship or the source of premium payments fails to respect the individual’s legal right to privacy regarding their specific insurance contract. The strategy of disclosing information while simultaneously notifying the client via email does not satisfy the regulatory requirement for prior consent. Opting for verbal confirmation on a recorded line lacks the formal documentation necessary to protect against future disputes or regulatory audits during compliance reviews.

Takeaway: Secure written authorization before disclosing nonpublic personal information to any third party to ensure compliance with federal privacy laws.

-

Question 17 of 30

17. Question

An insurance carrier is reviewing its portfolio of universal life and annuity products to ensure compliance with evolving regulatory expectations and internal risk targets. The management team is evaluating their product lifecycle management (PLM) framework, which covers everything from initial design to the eventual withdrawal of products from the market. Consider the following statements regarding professional product lifecycle management for US insurers:

I. Product development must align with the insurer’s risk appetite and capital requirements under Risk-Based Capital (RBC) standards.

II. The decline phase of a product lifecycle often involves closing the block to new business while maintaining service for existing policyholders.

III. Pricing assumptions established during the introduction phase must be periodically validated against actual mortality and lapse experience to ensure solvency.

IV. Once a life insurance product is approved by state insurance departments, the insurer is exempt from further suitability monitoring for that specific product line.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statements I, II, and III are correct. Risk-Based Capital (RBC) standards require US insurers to maintain capital levels commensurate with their specific risk profiles. Closing a block is a standard management technique for products that no longer meet profitability or strategic goals. Actuarial standards and state regulations require insurers to monitor actual experience against original pricing assumptions to maintain long-term financial stability.

Incorrect: The strategy of assuming exemption from suitability monitoring after initial state approval is incorrect. Regulators and the NAIC Suitability in Annuity Transactions Model Regulation emphasize that suitability is an ongoing obligation. Focusing only on the first two statements ignores the vital role of experience monitoring in maintaining solvency. Choosing combinations that include statement IV fails to account for the continuous oversight required in the US insurance market. Pursuing a framework that ignores post-approval monitoring creates significant regulatory and reputational risk.

Takeaway: Product lifecycle management integrates capital adequacy, experience monitoring, and ongoing suitability oversight to ensure long-term product viability.

Incorrect

Correct: Statements I, II, and III are correct. Risk-Based Capital (RBC) standards require US insurers to maintain capital levels commensurate with their specific risk profiles. Closing a block is a standard management technique for products that no longer meet profitability or strategic goals. Actuarial standards and state regulations require insurers to monitor actual experience against original pricing assumptions to maintain long-term financial stability.

Incorrect: The strategy of assuming exemption from suitability monitoring after initial state approval is incorrect. Regulators and the NAIC Suitability in Annuity Transactions Model Regulation emphasize that suitability is an ongoing obligation. Focusing only on the first two statements ignores the vital role of experience monitoring in maintaining solvency. Choosing combinations that include statement IV fails to account for the continuous oversight required in the US insurance market. Pursuing a framework that ignores post-approval monitoring creates significant regulatory and reputational risk.

Takeaway: Product lifecycle management integrates capital adequacy, experience monitoring, and ongoing suitability oversight to ensure long-term product viability.

-

Question 18 of 30

18. Question

The Board of Directors at a mid-sized U.S. life insurer is evaluating the company’s Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) framework following a period of significant market volatility. The Chief Risk Officer notes that while individual departments manage specific risks well, the firm lacks a unified view of how these risks correlate during extreme stress events. The board wants to ensure the framework aligns with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Risk Management and Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) Model Act. Which approach best demonstrates an effective ERM framework that satisfies both strategic objectives and regulatory expectations for a U.S. life insurer?

Correct

Correct: The NAIC ORSA Model Act requires insurers to maintain a risk management framework that identifies, assesses, monitors, and reports material risks. Integrating risk appetite with capital assessment ensures the firm remains solvent under various stress scenarios. This holistic approach allows the board to understand how different risks interact across the entire organization.

Incorrect: Relying solely on departmental silos fails to capture the interdependencies and correlations between different risk types across the enterprise. Focusing only on minimum Risk-Based Capital ratios ignores the forward-looking, self-assessment nature of a robust ERM program. The strategy of using purely qualitative registers lacks the rigorous quantitative analysis needed to evaluate capital adequacy during extreme market shifts.

Takeaway: Effective ERM requires an integrated, forward-looking assessment of all material risks and their impact on the insurer’s overall capital adequacy.

Incorrect

Correct: The NAIC ORSA Model Act requires insurers to maintain a risk management framework that identifies, assesses, monitors, and reports material risks. Integrating risk appetite with capital assessment ensures the firm remains solvent under various stress scenarios. This holistic approach allows the board to understand how different risks interact across the entire organization.

Incorrect: Relying solely on departmental silos fails to capture the interdependencies and correlations between different risk types across the enterprise. Focusing only on minimum Risk-Based Capital ratios ignores the forward-looking, self-assessment nature of a robust ERM program. The strategy of using purely qualitative registers lacks the rigorous quantitative analysis needed to evaluate capital adequacy during extreme market shifts.

Takeaway: Effective ERM requires an integrated, forward-looking assessment of all material risks and their impact on the insurer’s overall capital adequacy.

-

Question 19 of 30

19. Question

Marcus, a senior consultant, hosts a formal dinner at his primary residence for several high-value prospective clients to discuss a new service agreement. During the evening, a guest trips over an unsecured decorative cord in the hallway, sustaining a complex hip fracture that requires surgery and extensive rehabilitation. The guest files a lawsuit alleging negligence and seeking significant damages for medical expenses and lost income. Marcus maintains a standard HO-3 homeowners policy with a $300,000 liability limit and a Business Owners Policy (BOP) for his consulting firm with a $1,000,000 general liability limit. Given the nature of the event and the location of the injury, how should the liability coverage be analyzed under United States tort principles and standard insurance provisions?

Correct

Correct: The homeowners policy (HO-3) typically contains a business pursuits exclusion that denies coverage for liabilities arising from professional activities. Determining the primary purpose of the event is essential to establish whether the personal liability section or the commercial general liability policy must respond to the negligence claim.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the medical payments provision is insufficient because these limits are usually very low and do not provide a legal defense for the insured. The strategy of assuming the personal umbrella policy will automatically cover the loss ignores the requirement for underlying primary insurance to be in place for specific exposures. Choosing to apply strict liability is legally inaccurate as premises-related injuries generally require the plaintiff to prove a breach of duty or negligence. Focusing only on the location of the accident fails to account for the contractual exclusions regarding the nature of the activity being performed.

Takeaway: Proper liability planning requires aligning specific activities with the correct policy to avoid coverage gaps caused by business pursuit exclusions.

Incorrect

Correct: The homeowners policy (HO-3) typically contains a business pursuits exclusion that denies coverage for liabilities arising from professional activities. Determining the primary purpose of the event is essential to establish whether the personal liability section or the commercial general liability policy must respond to the negligence claim.

Incorrect: Relying solely on the medical payments provision is insufficient because these limits are usually very low and do not provide a legal defense for the insured. The strategy of assuming the personal umbrella policy will automatically cover the loss ignores the requirement for underlying primary insurance to be in place for specific exposures. Choosing to apply strict liability is legally inaccurate as premises-related injuries generally require the plaintiff to prove a breach of duty or negligence. Focusing only on the location of the accident fails to account for the contractual exclusions regarding the nature of the activity being performed.

Takeaway: Proper liability planning requires aligning specific activities with the correct policy to avoid coverage gaps caused by business pursuit exclusions.

-

Question 20 of 30

20. Question

An insurance product development team is reviewing the regulatory and functional characteristics of various flexible-premium life insurance products currently offered in the United States market. They are specifically analyzing the intersection of state insurance law and federal securities regulations, as well as the mechanics of interest crediting and policy guarantees. Consider the following statements regarding these product features:

I. Variable Universal Life (VUL) insurance is classified as a security and is subject to regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

II. Indexed Universal Life (IUL) policies typically utilize a participation rate and a cap to determine the interest credited to the policy’s cash value.

III. The incontestability clause allows an insurer to deny a death claim based on a material misrepresentation even if the policy has been in force for ten years.

IV. Secondary guarantees in Universal Life insurance allow the policy to remain in force even if the cash value is insufficient to cover monthly deductions.Which of the above statements are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statement I is accurate because Variable Universal Life (VUL) products are considered securities under federal law and require SEC registration. Statement II correctly identifies that Indexed Universal Life (IUL) uses participation rates and caps to calculate interest credits based on external index performance. Statement IV accurately describes secondary guarantees, also known as no-lapse guarantees, which protect the death benefit even if the cash value reaches zero.

Incorrect: The strategy of suggesting that the incontestability clause allows for denials after ten years is incorrect because this provision typically limits the insurer’s right to contest to two years. Focusing only on combinations that include the third statement fails to recognize that the incontestability clause does not apply to non-payment of premiums. Relying solely on combinations that omit the fourth statement ignores the significant role of secondary guarantees in modern Universal Life product innovation. Choosing to exclude the first statement overlooks the dual regulatory nature of variable insurance products in the United States.

Takeaway: VUL requires SEC oversight, while IUL and secondary guarantees are distinct innovations providing market-linked growth or death benefit stability.

Incorrect

Correct: Statement I is accurate because Variable Universal Life (VUL) products are considered securities under federal law and require SEC registration. Statement II correctly identifies that Indexed Universal Life (IUL) uses participation rates and caps to calculate interest credits based on external index performance. Statement IV accurately describes secondary guarantees, also known as no-lapse guarantees, which protect the death benefit even if the cash value reaches zero.

Incorrect: The strategy of suggesting that the incontestability clause allows for denials after ten years is incorrect because this provision typically limits the insurer’s right to contest to two years. Focusing only on combinations that include the third statement fails to recognize that the incontestability clause does not apply to non-payment of premiums. Relying solely on combinations that omit the fourth statement ignores the significant role of secondary guarantees in modern Universal Life product innovation. Choosing to exclude the first statement overlooks the dual regulatory nature of variable insurance products in the United States.

Takeaway: VUL requires SEC oversight, while IUL and secondary guarantees are distinct innovations providing market-linked growth or death benefit stability.

-

Question 21 of 30

21. Question

Sarah is a 45-year-old entrepreneur who recently launched a high-end boutique consulting firm in Chicago. She has significant debt from the startup phase and two young children. She is concerned about the financial impact her death would have on the business’s ability to repay loans and her family’s standard of living. She currently has a healthy lifestyle but works in a high-stress environment. Which risk management strategy is Sarah primarily employing if she decides to purchase a large term life insurance policy to cover her outstanding business loans and provide for her children’s education?

Correct

Correct: Risk transfer involves shifting the financial burden of a potential loss to another party, typically an insurance carrier, through a legal contract. By paying a premium, Sarah ensures the insurer bears the financial risk of her death. This is the fundamental principle of life insurance, where a small certain loss (the premium) is exchanged for the transfer of a large uncertain loss.

Incorrect: Choosing to restructure debt to minimize default likelihood describes a form of loss prevention or risk control rather than addressing the underlying mortality risk. The strategy of maintaining high savings to cover liabilities represents risk retention, where the individual or business assumes the full financial impact of the loss. Focusing only on wellness programs and stress management constitutes risk reduction, which aims to lower the frequency or severity of a loss but does not eliminate the financial impact if the loss occurs.

Takeaway: Risk transfer via insurance is the most effective method for managing low-frequency, high-severity risks like premature death.

Incorrect

Correct: Risk transfer involves shifting the financial burden of a potential loss to another party, typically an insurance carrier, through a legal contract. By paying a premium, Sarah ensures the insurer bears the financial risk of her death. This is the fundamental principle of life insurance, where a small certain loss (the premium) is exchanged for the transfer of a large uncertain loss.

Incorrect: Choosing to restructure debt to minimize default likelihood describes a form of loss prevention or risk control rather than addressing the underlying mortality risk. The strategy of maintaining high savings to cover liabilities represents risk retention, where the individual or business assumes the full financial impact of the loss. Focusing only on wellness programs and stress management constitutes risk reduction, which aims to lower the frequency or severity of a loss but does not eliminate the financial impact if the loss occurs.

Takeaway: Risk transfer via insurance is the most effective method for managing low-frequency, high-severity risks like premature death.

-

Question 22 of 30

22. Question

An advisor is evaluating a new Fixed Indexed Annuity (FIA) featuring a Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) for a client. The client is concerned about market volatility and seeks a balance between growth potential and lifetime income security. Consider the following statements regarding these complex annuity structures:

I. Fixed Indexed Annuities typically utilize participation rates or interest rate caps to determine the amount of interest credited based on an external index.

II. A Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) rider provides a contractually specified percentage of the benefit base for life, even if the contract’s account value is exhausted.

III. According to current federal regulations, all Fixed Indexed Annuities are categorized as securities and must be registered with the SEC under the Securities Act of 1933.

IV. The benefit base in a GMWB rider is equivalent to the contract’s cash surrender value and is available for a full lump-sum liquidation at any time.Which of the above statements is/are correct?

Correct

Correct: Statement I is correct because Fixed Indexed Annuities (FIAs) use caps, participation rates, or spreads to define how index performance translates into credited interest. Statement II is correct as it accurately describes the primary function of a Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) rider, which ensures lifetime income regardless of the actual account balance. These features allow insurers to manage market risk while providing clients with downside protection and guaranteed cash flow.

Incorrect: The strategy of classifying all FIAs as securities is incorrect because most are regulated as insurance products under state law rather than SEC registration. Relying on the assumption that the benefit base equals the cash surrender value is a common error in annuity analysis. The method of treating the benefit base as a liquid lump sum fails to recognize it is typically a non-liquid bookkeeping entry used only for income calculations. Focusing only on federal securities registration ignores the specific exemptions provided to insurance companies under current United States regulatory frameworks.

Takeaway: Distinguish between the income-generating benefit base and the actual cash value when evaluating complex annuity riders for retirement planning.

Incorrect

Correct: Statement I is correct because Fixed Indexed Annuities (FIAs) use caps, participation rates, or spreads to define how index performance translates into credited interest. Statement II is correct as it accurately describes the primary function of a Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) rider, which ensures lifetime income regardless of the actual account balance. These features allow insurers to manage market risk while providing clients with downside protection and guaranteed cash flow.

Incorrect: The strategy of classifying all FIAs as securities is incorrect because most are regulated as insurance products under state law rather than SEC registration. Relying on the assumption that the benefit base equals the cash surrender value is a common error in annuity analysis. The method of treating the benefit base as a liquid lump sum fails to recognize it is typically a non-liquid bookkeeping entry used only for income calculations. Focusing only on federal securities registration ignores the specific exemptions provided to insurance companies under current United States regulatory frameworks.

Takeaway: Distinguish between the income-generating benefit base and the actual cash value when evaluating complex annuity riders for retirement planning.

-

Question 23 of 30

23. Question

Robert is a business owner with a taxable estate valued at $15 million, including a $2 million life insurance policy currently payable to his estate. He wants to ensure the insurance proceeds are available to pay federal estate taxes and administrative expenses to avoid a forced liquidation of his business. However, he is concerned about the 5% statutory probate fees in his jurisdiction and the six-month delay typical of local court proceedings. Which strategy most effectively provides the required liquidity while shielding the insurance proceeds from the probate process and federal estate taxes?

Correct

Correct: Utilizing an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) as the beneficiary allows the death benefit to bypass the probate process entirely. This structure provides the estate with liquidity by permitting the trustee to purchase assets from the estate or provide loans. Under Internal Revenue Code Section 2042, this arrangement also keeps the proceeds out of the gross estate if structured correctly. This method ensures privacy and avoids the delays and costs associated with court-supervised administration.

Incorrect: Relying on the estate as the named beneficiary subjects the insurance proceeds to public record, executor fees, and the claims of general creditors. The strategy of naming individual children with informal side agreements lacks legal enforceability and may trigger secondary gift tax issues. Choosing a revocable trust that mandates the payment of estate obligations can cause the proceeds to be included in the gross estate for tax purposes. Focusing only on simplified probate procedures is ineffective because the policy value exceeds the statutory thresholds for such expedited court processes.

Takeaway: An ILIT provides liquidity to an estate while avoiding probate costs and maintaining the federal estate tax exclusion for insurance proceeds.

Incorrect

Correct: Utilizing an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) as the beneficiary allows the death benefit to bypass the probate process entirely. This structure provides the estate with liquidity by permitting the trustee to purchase assets from the estate or provide loans. Under Internal Revenue Code Section 2042, this arrangement also keeps the proceeds out of the gross estate if structured correctly. This method ensures privacy and avoids the delays and costs associated with court-supervised administration.

Incorrect: Relying on the estate as the named beneficiary subjects the insurance proceeds to public record, executor fees, and the claims of general creditors. The strategy of naming individual children with informal side agreements lacks legal enforceability and may trigger secondary gift tax issues. Choosing a revocable trust that mandates the payment of estate obligations can cause the proceeds to be included in the gross estate for tax purposes. Focusing only on simplified probate procedures is ineffective because the policy value exceeds the statutory thresholds for such expedited court processes.

Takeaway: An ILIT provides liquidity to an estate while avoiding probate costs and maintaining the federal estate tax exclusion for insurance proceeds.

-

Question 24 of 30

24. Question

A Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) is utilizing a new proprietary Artificial Intelligence (AI) platform to assist in developing life insurance recommendations for high-net-worth clients. The AI suggests a complex Variable Universal Life (VUL) policy for a client based on a multi-factor analysis of market volatility, tax projections, and the client’s stated legacy goals. However, the AI’s ‘black box’ logic makes it difficult to discern exactly how it weighted the client’s liquidity needs versus the death benefit maximization. The client’s family has expressed concerns about the complexity of the proposed structure. To remain compliant with SEC Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) and the NAIC Life Insurance and Annuities Suitability Model Regulation, how should the professional proceed with this AI-generated recommendation?

Correct

Correct: Under SEC Regulation Best Interest and NAIC Model 275, the producer must exercise reasonable diligence, care, and skill in making recommendations. AI tools are considered supportive technology that requires human oversight to prevent algorithmic bias or errors. The professional must validate that the output serves the client’s best interest by comparing it against the client’s actual financial situation. Maintaining transparency ensures the client understands the methodology and limitations of the advice provided.